In our previous article, we explored how clamp load—rather than just torque—is the true goal of a secure joint. However, to achieve the necessary clamp load without causing a failure, engineers must understand the physical limits of the fasteners they choose.

When discussing fastener strength, three specific terms are frequently used: tensile strength, yield strength, and proof load. Understanding the distinctions between these is vital for designing safe, reliable joints that perform as expected under stress.

Tensile Strength: The Breaking Point

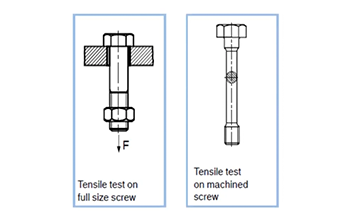

Tensile strength (or ultimate tensile strength) represents the maximum amount of force required to pull a bolt apart in an axial direction. This measurement is determined by pulling the bolt until it literally snaps. In standard testing, this is typically done as a straight pull without a nut attached to focus purely on the strength of the bolt material itself.

Yield Strength: The Limit of Elasticity

To understand yield strength, it is helpful to think of a bolt as a high-strength spring. When you apply a load, the bolt stretches. As long as you stay below the yield strength, the bolt will "bounce back" to its original length once the load is removed.

However, once you exceed the yield strength—which is typically 80% to 90% of the ultimate tensile strength—the bolt enters what engineers call the plastic region. In this state, the metal has been permanently deformed and will no longer return to its original form.

Proof Load: The Designer’s "Safe Zone"

Proof load is a value set slightly below the yield strength. It represents the maximum force that can be safely and repeatedly applied to a joint without causing permanent deformation.

For engineers designing clamp loads, the proof load is often the most important metric. By designing for a specific percentage of the proof load, you ensure the joint remains secure while staying safely away from the "plastic region" where the bolt would fail to provide consistent tension. This is especially critical for reusable joints that may be tightened and loosened multiple times.

The Special Case for Nuts

Interestingly, the terms tensile and yield strength do not technically apply to nuts because of their internal threads. Instead, nuts are rated primarily by proof load.

To test a nut's strength, a hardened mandrel is threaded through it and pulled to a minimum proof load. The load is held for 10 to 15 seconds and then released. A nut passes this test if it can then be backed off the mandrel by hand (or with minimal wrench force), proving the internal threads were not damaged or deformed by the stress.

Expert Guidance for Your Application

Selecting a fastener based on these strength ratings requires a balance between safety and performance. At Bossard, our application engineers—like Doug Jones, who has over 30 years of industry experience—work with manufacturers to ensure their joint designs never exceed these critical limits.